Wagner’s ‘Parsifal’ Returns to Save the World—Maybe Even the Met

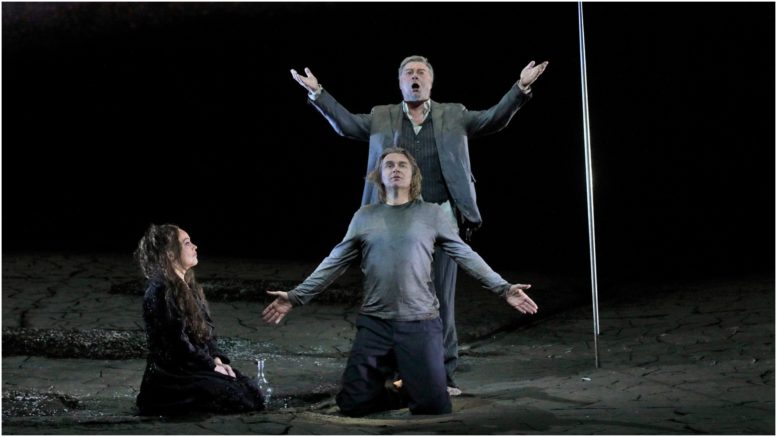

Parsifal (Klaus Florian Vogt) returns to the Grail Kingdom to heal the ailing Amfortas (Pater Mattei). Ken Howard / Met Opera

Call in sick at work. Hire a sitter for your kids, dogs or significant other. Take a long nap, then slam back a triple espresso. That may sound like a daunting prep for an evening at the opera, but the Met’s stunning revival of Richard Wagner’s Parsifal is more than just highbrow entertainment. It’s an artistic experience that could change your life.

That’s just what the composer intended this 1882 epic to accomplish. From a swath of medieval source material about a naïve young boy’s path to the exalted rank of guardian of the Holy Grail, he devised a massive drama that not only relates an archetypal hero myth but proposes a new belief system for Western society, fusing Catholicism, Buddhism, Schopenhauerian philosophy, animal rights and Earth religion.

But you don’t have to convert to be overwhelmed by this Parsifal, especially as visualized in the Met’s pensive, immaculately edited production by François Girard. He transposes the action from the Middle Ages to an eerie dystopian near future, conjuring a fundamentalist, sex-negative social order not unlike that in The Handmaid’s Tale.

Girard’s vision was terrifying enough five years ago when the production premiered, but now its depiction of the total breakdown of relationships between the sexes feels almost torn from the headlines. Parsifal’s mission becomes something much more real and necessary than the rescue of a magical spear: he has to reunite a society splintered into mindless male cults and soulless female militias.

Several of the singers in this season’s cast are veterans of the Met’s 2013 incarnation of the work, and, excellent as they were then, they have all gained depth and subtlety in the time since.

Most impressive in his development is the bass René Pape, whose long role of Gurnemanz consists largely of filling in the opera’s complex back story. If his luxurious bass now reveals an occasional trace of scratch, that only add a patina to its beauty. More to the point, his declamation never feels oratorial or formal; every word and every inflection is so natural and intimate the whole performance feels like it’s overheard.

As the malevolent Klingsor, Evgeny Nikitin filed his elegant bass-baritone down to an animalistic snarl. The character of the sorcerer was all the more terrifying for his lack of self-awareness: he was not merely evil but possessed by a demon.

Surely the centerpiece of this performance, though, is Peter Mattei as the tormented Grail King Amfortas. It is this character’s moral failing (and his subsequent tortured and unending remorse) that drives this story, and, strangely enough, the sheer sensual beauty of Mattei’s baritone made the tragedy almost unbearably touching. Even his wildest screams of pain never turned ugly, communicating the insight that even the most abased of creatures is still human, still cherishable.

Mattei’s performance, one of the strongest I’ve ever seen in the theater, at first cast a bit of a shadow over the two new additions to the cast, but they hold their own. Soprano Evelyn Herlitzius fascinated as the enigmatic shape-shifter Kundry, her “dialed up to 11” acting delineating the character’s curse of experiencing eternal life as a series of devious performances. Her muscular voice admittedly has quite a few miles on it, but her sterling commitment made even a few yelps standing in for high notes sound organic.

It is altogether fitting that in so ambiguous a work as Parsifal, the title role should be performed the paradox that is Klaus Florian Vogt. You would think this hulking blond giant would emit a mighty roar, but instead what emerges is a light, heady tenor only slightly darker than a boy soprano’s piping.

Vogt is thus simultaneously a child and a man, a sort of time-lapse photograph of the hero’s journey. Though in affect he is the polar opposite of Jonas Kaufmann’s glamorously moody hero as heard in 2013. Vogt is, if anything, more effective in the part, more intensely concentrated and, I thought, more cognizant of the awesome responsibility the character assumes.

And yet the most moving epiphany of the night was the conducting of the Met’s new music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin, sweetly poetic and, even in the score’s direst moments, glowing with hope. As in last season’s Fliegende Holländer, Nézet-Séguin lent the music an irresistible forward motion, never rushed, but rather with the verve of a great raconteur relating the most fascinating story in the world. When he took his bow, the great roar of bravos from the Met audience felt like…well, an anointing.

The Met has taken some hard knocks in recent months and years, and yet, after last night’s Parsifal, you can’t help feeling hopeful. The company looks like it’s going to survive, and Yannick Nézet-Séguin is going to be its savior.

Parsifal (Klaus Florian Vogt) returns to the Grail Kingdom to heal the ailing Amfortas (Pater Mattei). Ken Howard / Met Opera

Call in sick at work. Hire a sitter for your kids, dogs or significant other. Take a long nap, then slam back a triple espresso. That may sound like a daunting prep for an evening at the opera, but the Met’s stunning revival of Richard Wagner’s Parsifal is more than just highbrow entertainment. It’s an artistic experience that could change your life.

That’s just what the composer intended this 1882 epic to accomplish. From a swath of medieval source material about a naïve young boy’s path to the exalted rank of guardian of the Holy Grail, he devised a massive drama that not only relates an archetypal hero myth but proposes a new belief system for Western society, fusing Catholicism, Buddhism, Schopenhauerian philosophy, animal rights and Earth religion.

But you don’t have to convert to be overwhelmed by this Parsifal, especially as visualized in the Met’s pensive, immaculately edited production by François Girard. He transposes the action from the Middle Ages to an eerie dystopian near future, conjuring a fundamentalist, sex-negative social order not unlike that in The Handmaid’s Tale.

Girard’s vision was terrifying enough five years ago when the production premiered, but now its depiction of the total breakdown of relationships between the sexes feels almost torn from the headlines. Parsifal’s mission becomes something much more real and necessary than the rescue of a magical spear: he has to reunite a society splintered into mindless male cults and soulless female militias.

Several of the singers in this season’s cast are veterans of the Met’s 2013 incarnation of the work, and, excellent as they were then, they have all gained depth and subtlety in the time since.

Most impressive in his development is the bass René Pape, whose long role of Gurnemanz consists largely of filling in the opera’s complex back story. If his luxurious bass now reveals an occasional trace of scratch, that only add a patina to its beauty. More to the point, his declamation never feels oratorial or formal; every word and every inflection is so natural and intimate the whole performance feels like it’s overheard.

As the malevolent Klingsor, Evgeny Nikitin filed his elegant bass-baritone down to an animalistic snarl. The character of the sorcerer was all the more terrifying for his lack of self-awareness: he was not merely evil but possessed by a demon.

Surely the centerpiece of this performance, though, is Peter Mattei as the tormented Grail King Amfortas. It is this character’s moral failing (and his subsequent tortured and unending remorse) that drives this story, and, strangely enough, the sheer sensual beauty of Mattei’s baritone made the tragedy almost unbearably touching. Even his wildest screams of pain never turned ugly, communicating the insight that even the most abased of creatures is still human, still cherishable.

Mattei’s performance, one of the strongest I’ve ever seen in the theater, at first cast a bit of a shadow over the two new additions to the cast, but they hold their own. Soprano Evelyn Herlitzius fascinated as the enigmatic shape-shifter Kundry, her “dialed up to 11” acting delineating the character’s curse of experiencing eternal life as a series of devious performances. Her muscular voice admittedly has quite a few miles on it, but her sterling commitment made even a few yelps standing in for high notes sound organic.

It is altogether fitting that in so ambiguous a work as Parsifal, the title role should be performed the paradox that is Klaus Florian Vogt. You would think this hulking blond giant would emit a mighty roar, but instead what emerges is a light, heady tenor only slightly darker than a boy soprano’s piping.

Vogt is thus simultaneously a child and a man, a sort of time-lapse photograph of the hero’s journey. Though in affect he is the polar opposite of Jonas Kaufmann’s glamorously moody hero as heard in 2013. Vogt is, if anything, more effective in the part, more intensely concentrated and, I thought, more cognizant of the awesome responsibility the character assumes.

And yet the most moving epiphany of the night was the conducting of the Met’s new music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin, sweetly poetic and, even in the score’s direst moments, glowing with hope. As in last season’s Fliegende Holländer, Nézet-Séguin lent the music an irresistible forward motion, never rushed, but rather with the verve of a great raconteur relating the most fascinating story in the world. When he took his bow, the great roar of bravos from the Met audience felt like…well, an anointing.

The Met has taken some hard knocks in recent months and years, and yet, after last night’s Parsifal, you can’t help feeling hopeful. The company looks like it’s going to survive, and Yannick Nézet-Séguin is going to be its savior.

Parsifal (Klaus Florian Vogt) returns to the Grail Kingdom to heal the ailing Amfortas (Pater Mattei). Ken Howard / Met Opera

Call in sick at work. Hire a sitter for your kids, dogs or significant other. Take a long nap, then slam back a triple espresso. That may sound like a daunting prep for an evening at the opera, but the Met’s stunning revival of Richard Wagner’s Parsifal is more than just highbrow entertainment. It’s an artistic experience that could change your life.

That’s just what the composer intended this 1882 epic to accomplish. From a swath of medieval source material about a naïve young boy’s path to the exalted rank of guardian of the Holy Grail, he devised a massive drama that not only relates an archetypal hero myth but proposes a new belief system for Western society, fusing Catholicism, Buddhism, Schopenhauerian philosophy, animal rights and Earth religion.

But you don’t have to convert to be overwhelmed by this Parsifal, especially as visualized in the Met’s pensive, immaculately edited production by François Girard. He transposes the action from the Middle Ages to an eerie dystopian near future, conjuring a fundamentalist, sex-negative social order not unlike that in The Handmaid’s Tale.

Girard’s vision was terrifying enough five years ago when the production premiered, but now its depiction of the total breakdown of relationships between the sexes feels almost torn from the headlines. Parsifal’s mission becomes something much more real and necessary than the rescue of a magical spear: he has to reunite a society splintered into mindless male cults and soulless female militias.

Several of the singers in this season’s cast are veterans of the Met’s 2013 incarnation of the work, and, excellent as they were then, they have all gained depth and subtlety in the time since.

Most impressive in his development is the bass René Pape, whose long role of Gurnemanz consists largely of filling in the opera’s complex back story. If his luxurious bass now reveals an occasional trace of scratch, that only add a patina to its beauty. More to the point, his declamation never feels oratorial or formal; every word and every inflection is so natural and intimate the whole performance feels like it’s overheard.

As the malevolent Klingsor, Evgeny Nikitin filed his elegant bass-baritone down to an animalistic snarl. The character of the sorcerer was all the more terrifying for his lack of self-awareness: he was not merely evil but possessed by a demon.

Surely the centerpiece of this performance, though, is Peter Mattei as the tormented Grail King Amfortas. It is this character’s moral failing (and his subsequent tortured and unending remorse) that drives this story, and, strangely enough, the sheer sensual beauty of Mattei’s baritone made the tragedy almost unbearably touching. Even his wildest screams of pain never turned ugly, communicating the insight that even the most abased of creatures is still human, still cherishable.

Mattei’s performance, one of the strongest I’ve ever seen in the theater, at first cast a bit of a shadow over the two new additions to the cast, but they hold their own. Soprano Evelyn Herlitzius fascinated as the enigmatic shape-shifter Kundry, her “dialed up to 11” acting delineating the character’s curse of experiencing eternal life as a series of devious performances. Her muscular voice admittedly has quite a few miles on it, but her sterling commitment made even a few yelps standing in for high notes sound organic.

It is altogether fitting that in so ambiguous a work as Parsifal, the title role should be performed the paradox that is Klaus Florian Vogt. You would think this hulking blond giant would emit a mighty roar, but instead what emerges is a light, heady tenor only slightly darker than a boy soprano’s piping.

Vogt is thus simultaneously a child and a man, a sort of time-lapse photograph of the hero’s journey. Though in affect he is the polar opposite of Jonas Kaufmann’s glamorously moody hero as heard in 2013. Vogt is, if anything, more effective in the part, more intensely concentrated and, I thought, more cognizant of the awesome responsibility the character assumes.

And yet the most moving epiphany of the night was the conducting of the Met’s new music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin, sweetly poetic and, even in the score’s direst moments, glowing with hope. As in last season’s Fliegende Holländer, Nézet-Séguin lent the music an irresistible forward motion, never rushed, but rather with the verve of a great raconteur relating the most fascinating story in the world. When he took his bow, the great roar of bravos from the Met audience felt like…well, an anointing.

The Met has taken some hard knocks in recent months and years, and yet, after last night’s Parsifal, you can’t help feeling hopeful. The company looks like it’s going to survive, and Yannick Nézet-Séguin is going to be its savior.

Metropolitan Opera 2017-18 Review – Parsifal: A Brilliant Cast Shines In Met’s Greatest Production Of Last Decade

(Credit: Metropolitan Opera)

The world is divided into men and women. And only the unification of these two sides, through mutual understanding and respect can bridge the gap and bring about a new world full of equality.

Sounds familiar right? It was what François Girard saw prior to 2013, and his vision remains ever true to this day. Perhaps even more prevalent.

It is this kind of vision and understanding of human nature that makes his “Parsifal” arguably the single greatest production to arrive at the Metropolitan Opera in the last 20 or so years. No joke.

And for the second straight time since the production opened in 2013, the company has put together a superstar cast that adds to the genius of the mis-en-scene.

Let’s dig in.

Prescient Vision

The lights go out and we are greeted with a curtain showcasing the Met auditorium, almost as if a mirror were being held up to the audience. Then the curtain rises and a sea of people, clad in black appear facing the audience. Among them is Parsifal. The group features both men and women, though they seem to be moving in different directions; only Parsifal looks lost as to where to go. The men remove their black clothing and ties, revealing white undergarments, emphasizing themselves as pure knights of the grail. Then they move stage left and form a circular configuration of chairs; the woman go in the opposite direction to a side separated by a fissure in the ground. This division dominates the work and portrays a divisive civilization, one in which men and women are at odds with one another. Given the current nature of our society, this opera could not be more revelant in this interpretation.

Throughout Act one, we get the ritual of the grail showcased amidst video a planet, clouds, deep space, and even hints of a human body that on closer inspection can look like the bread that Christ associates with his flesh. Or is it the sin of the world that is constantly mentioned in the opera? The voice of Titurel booms throughout the theater almost suggesting God. This portrayal takes on more prevalent meaning when Gurnemanz states in Act three that Titurel died “like any other man;” the subversion of God in a modern society.

The opera’s theme of male-female divison is embedded in its very structure. While Act one clearly belongs to the men, the second act is dominated by women and the final one, at least in this version, showcases a reconciliation. The second act sees the manipulation of the women from the opening act, which Girard has previously noted as “aspects” of Kundry, by the villainous Klingsor. He has them do his bidding, and its pretty sexual in nature. No doubt watching the man toss blood around from the inside of a female genitalia (that is where Act two takes place, right?) is rather uneasy to watch in the current social mileu. That Parsifal comes in and liberates everyone might strike some as wrong for a number of reasons, but Girard isn’t trying to destroy the opera’s text either. But he ultimately does make a brilliant move in the final act to lend it social relevance and acceptance.

Act three reverts to the opening set, but with the world in abrupt turmoil. Time has passed and the knights have disbanded, forced to eat whatever they can find. A burial is taking place and the rules and divisions established in the opening act are completely eroded. Only Kundry, the symbol of “sin” in the world, is unable to cross the gap.

Then Parsifal arrives in an incredible theatrical coup, his silhouette generating a sense of mystery. As he draws nearer, he comes into the light and becomes clearer. The man who was a mystery is now the redeemer of all. From there the work moves into pure sublime beauty, Gurnemanz and Kundry washing the feet and brow of the weary Parsifal as he is hailed King and leader of the knights. Then Parsifal proceeds to help Kundry cross the chasm and be absolved of sin.

And to clinch it all, Kundry is the one to open the grail, a move often left to the men. While she dies, her evolution throughout the production explores women being allowed to return to their rightful place – as equals of men. In the final image of the night, as Parsifal lifts up the chalice, the stage is littered with men and woman together. They wear similar clothing and the gap in the ground is barely recognizable. A new society begins with the inequality done away with.

But Girard isn’t even finished there because in the very final moment of the piece, with Parsifal lifting the chalice, two figures stand amidst the kneeled crowd. One is Amfortas, the former King whose sin caused the turmoil of the brotherhood. The other is a woman clad in black. There are a few people still porting the black, but most are clad in white. The woman stands out amidst this crowd. And with the curtain dropping, Parsifal turns and glances in her direction. It leaves the viewer with a lot of questions. Is this a new Kundry and is Parsifal to follow Amfortas’ path, resetting the cycle back? Or is this the sign of progress? Of a woman set to come and rule alongside Parsifal? It is a brilliant touch that avoids leaving this seemingly positive outlook filled with a tinge of ambiguity. Life isn’t so simple, afterall.

One final note – after seeing blood flow throughout the chasm in the opening act, the final imagery showcases water. Human’s open wound has been closed and the sacred fountain restored.

Return of the Titans

The cast is absolutely sensational in every respect. Four years ago, Peter Mattei and René Pape reigned supreme as Amfortas and Gurnemanz respectively.

On Monday, they were even better.

Mattei was an absolute scene stealer every single time he was onstage, his voice ringing out imperiously into the cavernous Met. It’s almost impossible to believe that he didn’t have a microphone, so gargantuan was the ring throughout the theater. It was heartbreaking to hear this glorious sound usher out one pained phrase after another and yet Mattei always sustained incredible sense of technical precision. He built up his monologue so beautifully, each phrase more tortured than the previous one that his cries of “Erbarmen! Erbarmen!” were sublime climaxes to it all. He had even greater desperation, but also a more tragic sense of loss in the third act, jumping into the tomb in the ground, his movements more erratic at times and yet his voice softer and more muted. But the moments where he is called upon to blast out in increased pain showed him even more potent and forceful vocally.

The same could be said for Pape, who was clarity embodied as Gurnemanz. The character’s main role is as the narrator of the opera and the emotional range is limited at best in the opening act. However, his gentle nature came through in the final act in his interactions with Parsifal, his gloriously rich bass sound at its finest. His physicality was also rather telling, Pape imbuing the character with a signature pacing movement throughout the opening act, only to show that same movement impaired and weaker in the final third of the opera. It added to the sense of Gurnemanz being somehow broken over the failures of the knights.

Evgeny Nikitin returned to the role of Klingsor and relished it. His voice was pointed, vicious and his movements were in direct contrast with everyone else onstage. He had no qualms about moving with snakelike precision. His scene with Evelyn Herlitzius’ Kundry is simply exquisite in how the two voices blasted sound at one another in visceral confrontation.

Ever Thrilling & Fascinating

Speaking of Herlitzius, the German soprano was making her North American and Metropolitan Opera debut. Her voice isn’t a pretty sound whatsoever. One could even define it as abrasive, with a sharp vibrato that wobbles a bit in the upper range. But one could never accuse her of being boring or uninteresting. In fact, she is the complete opposite. Her Kundry was completely unhinged from the start, her exaggerated laughs and moans always off-putting for the viewer, but adding to the interest. You always wanted to know what she was going for and where she was going with the character. And she showed some tremendous range. She was overpowered in her fight with Klingsor, even if vocally she gave it her all and put up quite the fight. In her seduction of Parsifal, she was alluring and sensual. But when rejected, she was the embodiment of “hell hath no fury as a woman scorned,” her singing blistering in its power and strength. It was endlessly thrilling to see her rise into the soprano stratosphere, even if it wasn’t always pretty.

Victory Through Compassion, Not Power

Speaking of pretty, let’s talk about Klaus Florian Vogt, whose interpretation was simply beautiful. To some his voice seems out of place in a Wagner opera. I’ve even heard of him as being a “pushed-up Tamino.” It might all be completely right and at the same time it doesn’t matter. When writing his operas, Wagner called for bel canto style singing in the vein of his beloved Bellini. We don’t usually get that from tenors, mainly because the heavy and thick voices we are accustomed to can’t quite carry lines in that manner or with that “bel canto” beauty. But Vogt’s does. Moreover, his voice carries tremendous weight that cuts through the orchestra quite splendidly. His “Amfortas! Die Wunde!” was a perfect example of this, the delicate timbre suddenly thick and potent. But the true beauty of a passage such as this one was the sense of expansion of the line, giving the passage true anguish and introspection. And because of the complexion of his voice, Vogt could add nuance and layers to his Parsifal as a true “innocent fool.” Whereas other heroic tenors can’t genuinely sound like an innocent or pure man, Vogt can and he used it to his full advantage. One such example was the climactic showdown with Klingsor where with his hand raised he stops the wizard in his tracks and utters, “Mit diesem Zeichen bann’ich deinen Zauber.” He could have taken the approach of belting out this power declaration of victory, but instead opted for gentleness. At the end of the opera, Parsifal wins and unites the world through compassion, not strength. And in his greatest moment of victory over evil, he wins not through brute force, but through this very same emotion. The choice by Vogt is potent and insightful all the same. He brings a similar vocal quality in his final scene, furthering the point of Parsifal’s victory coming through compassion and love and not the violence and might of such Wagnerian heroes as Siegfried or Tristan (ironically, these heroes ultimately find death after said victories).

Musical Introspection

It is often said that, in Schopenhauerian terms, Wagner’s music could be described as “the will” personified. But in “Parsifal,” one might be more inclined to say that the majority of the music is the “abnegation” of said will. Instead of incessant brooding and propulsive momentum, Wagner’s last score is gentle, subdued, and even ponderous. It doesn’t move anywhere all that quickly (except for Act two), more interested in living in the moment, as Gurnemanz notes, where time becomes space. And it seems that maestro Yannick Nézet-Séguin approaches the score with this gentle nature in mind. His tempi tend to be broad, particularly when Wagner calls for lengthy pauses. You could feel the spacing throughout the prelude, the silences introspective and invitations to dig deeper. But what made his interpretation truly unique was the overall restraint you could feel. The entrance of the knights to close out the opening act did not emphasize the march-like nature that is often given grandiosity in other interpretations. Here it remained subdued, the transition more focused on the shift in mood. That isn’t to say that he wasn’t aggressive or didn’t push the Met Orchestra to its full voluminous potential. The music frayed and blistered powerfully throughout the second act as the tensions grew. But it all came back to the level of sublime tenderness in the final act, the final phrases simply divine.

There were a few orchestral misfires to be honest, with the brass section audibly uncomfortable and out of sync on some cues, but this is likely to improve with each passing performance.

So yes, this night was truly mesmerizing and for the second time in as many tries the Metropolitan Opera has a true winner with François Girard’s “Parsifal.” It is undeniably the finest Wagner production at the Met right now and the hope is that the director will come back and direct another production at such a high level. It also helps to have such an incredible cast in the ranks.

(Credit: Metropolitan Opera)

The world is divided into men and women. And only the unification of these two sides, through mutual understanding and respect can bridge the gap and bring about a new world full of equality.

Sounds familiar right? It was what François Girard saw prior to 2013, and his vision remains ever true to this day. Perhaps even more prevalent.

It is this kind of vision and understanding of human nature that makes his “Parsifal” arguably the single greatest production to arrive at the Metropolitan Opera in the last 20 or so years. No joke.

And for the second straight time since the production opened in 2013, the company has put together a superstar cast that adds to the genius of the mis-en-scene.

Let’s dig in.

Prescient Vision

The lights go out and we are greeted with a curtain showcasing the Met auditorium, almost as if a mirror were being held up to the audience. Then the curtain rises and a sea of people, clad in black appear facing the audience. Among them is Parsifal. The group features both men and women, though they seem to be moving in different directions; only Parsifal looks lost as to where to go. The men remove their black clothing and ties, revealing white undergarments, emphasizing themselves as pure knights of the grail. Then they move stage left and form a circular configuration of chairs; the woman go in the opposite direction to a side separated by a fissure in the ground. This division dominates the work and portrays a divisive civilization, one in which men and women are at odds with one another. Given the current nature of our society, this opera could not be more revelant in this interpretation.

Throughout Act one, we get the ritual of the grail showcased amidst video a planet, clouds, deep space, and even hints of a human body that on closer inspection can look like the bread that Christ associates with his flesh. Or is it the sin of the world that is constantly mentioned in the opera? The voice of Titurel booms throughout the theater almost suggesting God. This portrayal takes on more prevalent meaning when Gurnemanz states in Act three that Titurel died “like any other man;” the subversion of God in a modern society.

The opera’s theme of male-female divison is embedded in its very structure. While Act one clearly belongs to the men, the second act is dominated by women and the final one, at least in this version, showcases a reconciliation. The second act sees the manipulation of the women from the opening act, which Girard has previously noted as “aspects” of Kundry, by the villainous Klingsor. He has them do his bidding, and its pretty sexual in nature. No doubt watching the man toss blood around from the inside of a female genitalia (that is where Act two takes place, right?) is rather uneasy to watch in the current social mileu. That Parsifal comes in and liberates everyone might strike some as wrong for a number of reasons, but Girard isn’t trying to destroy the opera’s text either. But he ultimately does make a brilliant move in the final act to lend it social relevance and acceptance.

Act three reverts to the opening set, but with the world in abrupt turmoil. Time has passed and the knights have disbanded, forced to eat whatever they can find. A burial is taking place and the rules and divisions established in the opening act are completely eroded. Only Kundry, the symbol of “sin” in the world, is unable to cross the gap.

Then Parsifal arrives in an incredible theatrical coup, his silhouette generating a sense of mystery. As he draws nearer, he comes into the light and becomes clearer. The man who was a mystery is now the redeemer of all. From there the work moves into pure sublime beauty, Gurnemanz and Kundry washing the feet and brow of the weary Parsifal as he is hailed King and leader of the knights. Then Parsifal proceeds to help Kundry cross the chasm and be absolved of sin.

And to clinch it all, Kundry is the one to open the grail, a move often left to the men. While she dies, her evolution throughout the production explores women being allowed to return to their rightful place – as equals of men. In the final image of the night, as Parsifal lifts up the chalice, the stage is littered with men and woman together. They wear similar clothing and the gap in the ground is barely recognizable. A new society begins with the inequality done away with.

But Girard isn’t even finished there because in the very final moment of the piece, with Parsifal lifting the chalice, two figures stand amidst the kneeled crowd. One is Amfortas, the former King whose sin caused the turmoil of the brotherhood. The other is a woman clad in black. There are a few people still porting the black, but most are clad in white. The woman stands out amidst this crowd. And with the curtain dropping, Parsifal turns and glances in her direction. It leaves the viewer with a lot of questions. Is this a new Kundry and is Parsifal to follow Amfortas’ path, resetting the cycle back? Or is this the sign of progress? Of a woman set to come and rule alongside Parsifal? It is a brilliant touch that avoids leaving this seemingly positive outlook filled with a tinge of ambiguity. Life isn’t so simple, afterall.

One final note – after seeing blood flow throughout the chasm in the opening act, the final imagery showcases water. Human’s open wound has been closed and the sacred fountain restored.

Return of the Titans

The cast is absolutely sensational in every respect. Four years ago, Peter Mattei and René Pape reigned supreme as Amfortas and Gurnemanz respectively.

On Monday, they were even better.

Mattei was an absolute scene stealer every single time he was onstage, his voice ringing out imperiously into the cavernous Met. It’s almost impossible to believe that he didn’t have a microphone, so gargantuan was the ring throughout the theater. It was heartbreaking to hear this glorious sound usher out one pained phrase after another and yet Mattei always sustained incredible sense of technical precision. He built up his monologue so beautifully, each phrase more tortured than the previous one that his cries of “Erbarmen! Erbarmen!” were sublime climaxes to it all. He had even greater desperation, but also a more tragic sense of loss in the third act, jumping into the tomb in the ground, his movements more erratic at times and yet his voice softer and more muted. But the moments where he is called upon to blast out in increased pain showed him even more potent and forceful vocally.

The same could be said for Pape, who was clarity embodied as Gurnemanz. The character’s main role is as the narrator of the opera and the emotional range is limited at best in the opening act. However, his gentle nature came through in the final act in his interactions with Parsifal, his gloriously rich bass sound at its finest. His physicality was also rather telling, Pape imbuing the character with a signature pacing movement throughout the opening act, only to show that same movement impaired and weaker in the final third of the opera. It added to the sense of Gurnemanz being somehow broken over the failures of the knights.

Evgeny Nikitin returned to the role of Klingsor and relished it. His voice was pointed, vicious and his movements were in direct contrast with everyone else onstage. He had no qualms about moving with snakelike precision. His scene with Evelyn Herlitzius’ Kundry is simply exquisite in how the two voices blasted sound at one another in visceral confrontation.

Ever Thrilling & Fascinating

Speaking of Herlitzius, the German soprano was making her North American and Metropolitan Opera debut. Her voice isn’t a pretty sound whatsoever. One could even define it as abrasive, with a sharp vibrato that wobbles a bit in the upper range. But one could never accuse her of being boring or uninteresting. In fact, she is the complete opposite. Her Kundry was completely unhinged from the start, her exaggerated laughs and moans always off-putting for the viewer, but adding to the interest. You always wanted to know what she was going for and where she was going with the character. And she showed some tremendous range. She was overpowered in her fight with Klingsor, even if vocally she gave it her all and put up quite the fight. In her seduction of Parsifal, she was alluring and sensual. But when rejected, she was the embodiment of “hell hath no fury as a woman scorned,” her singing blistering in its power and strength. It was endlessly thrilling to see her rise into the soprano stratosphere, even if it wasn’t always pretty.

Victory Through Compassion, Not Power

Speaking of pretty, let’s talk about Klaus Florian Vogt, whose interpretation was simply beautiful. To some his voice seems out of place in a Wagner opera. I’ve even heard of him as being a “pushed-up Tamino.” It might all be completely right and at the same time it doesn’t matter. When writing his operas, Wagner called for bel canto style singing in the vein of his beloved Bellini. We don’t usually get that from tenors, mainly because the heavy and thick voices we are accustomed to can’t quite carry lines in that manner or with that “bel canto” beauty. But Vogt’s does. Moreover, his voice carries tremendous weight that cuts through the orchestra quite splendidly. His “Amfortas! Die Wunde!” was a perfect example of this, the delicate timbre suddenly thick and potent. But the true beauty of a passage such as this one was the sense of expansion of the line, giving the passage true anguish and introspection. And because of the complexion of his voice, Vogt could add nuance and layers to his Parsifal as a true “innocent fool.” Whereas other heroic tenors can’t genuinely sound like an innocent or pure man, Vogt can and he used it to his full advantage. One such example was the climactic showdown with Klingsor where with his hand raised he stops the wizard in his tracks and utters, “Mit diesem Zeichen bann’ich deinen Zauber.” He could have taken the approach of belting out this power declaration of victory, but instead opted for gentleness. At the end of the opera, Parsifal wins and unites the world through compassion, not strength. And in his greatest moment of victory over evil, he wins not through brute force, but through this very same emotion. The choice by Vogt is potent and insightful all the same. He brings a similar vocal quality in his final scene, furthering the point of Parsifal’s victory coming through compassion and love and not the violence and might of such Wagnerian heroes as Siegfried or Tristan (ironically, these heroes ultimately find death after said victories).

Musical Introspection

It is often said that, in Schopenhauerian terms, Wagner’s music could be described as “the will” personified. But in “Parsifal,” one might be more inclined to say that the majority of the music is the “abnegation” of said will. Instead of incessant brooding and propulsive momentum, Wagner’s last score is gentle, subdued, and even ponderous. It doesn’t move anywhere all that quickly (except for Act two), more interested in living in the moment, as Gurnemanz notes, where time becomes space. And it seems that maestro Yannick Nézet-Séguin approaches the score with this gentle nature in mind. His tempi tend to be broad, particularly when Wagner calls for lengthy pauses. You could feel the spacing throughout the prelude, the silences introspective and invitations to dig deeper. But what made his interpretation truly unique was the overall restraint you could feel. The entrance of the knights to close out the opening act did not emphasize the march-like nature that is often given grandiosity in other interpretations. Here it remained subdued, the transition more focused on the shift in mood. That isn’t to say that he wasn’t aggressive or didn’t push the Met Orchestra to its full voluminous potential. The music frayed and blistered powerfully throughout the second act as the tensions grew. But it all came back to the level of sublime tenderness in the final act, the final phrases simply divine.

There were a few orchestral misfires to be honest, with the brass section audibly uncomfortable and out of sync on some cues, but this is likely to improve with each passing performance.

So yes, this night was truly mesmerizing and for the second time in as many tries the Metropolitan Opera has a true winner with François Girard’s “Parsifal.” It is undeniably the finest Wagner production at the Met right now and the hope is that the director will come back and direct another production at such a high level. It also helps to have such an incredible cast in the ranks.

(Credit: Metropolitan Opera)

(Credit: Metropolitan Opera)

The world is divided into men and women. And only the unification of these two sides, through mutual understanding and respect can bridge the gap and bring about a new world full of equality.

Sounds familiar right? It was what François Girard saw prior to 2013, and his vision remains ever true to this day. Perhaps even more prevalent.

It is this kind of vision and understanding of human nature that makes his “Parsifal” arguably the single greatest production to arrive at the Metropolitan Opera in the last 20 or so years. No joke.

And for the second straight time since the production opened in 2013, the company has put together a superstar cast that adds to the genius of the mis-en-scene.

Let’s dig in.

Prescient Vision

The lights go out and we are greeted with a curtain showcasing the Met auditorium, almost as if a mirror were being held up to the audience. Then the curtain rises and a sea of people, clad in black appear facing the audience. Among them is Parsifal. The group features both men and women, though they seem to be moving in different directions; only Parsifal looks lost as to where to go. The men remove their black clothing and ties, revealing white undergarments, emphasizing themselves as pure knights of the grail. Then they move stage left and form a circular configuration of chairs; the woman go in the opposite direction to a side separated by a fissure in the ground. This division dominates the work and portrays a divisive civilization, one in which men and women are at odds with one another. Given the current nature of our society, this opera could not be more revelant in this interpretation.

Throughout Act one, we get the ritual of the grail showcased amidst video a planet, clouds, deep space, and even hints of a human body that on closer inspection can look like the bread that Christ associates with his flesh. Or is it the sin of the world that is constantly mentioned in the opera? The voice of Titurel booms throughout the theater almost suggesting God. This portrayal takes on more prevalent meaning when Gurnemanz states in Act three that Titurel died “like any other man;” the subversion of God in a modern society.

The opera’s theme of male-female divison is embedded in its very structure. While Act one clearly belongs to the men, the second act is dominated by women and the final one, at least in this version, showcases a reconciliation. The second act sees the manipulation of the women from the opening act, which Girard has previously noted as “aspects” of Kundry, by the villainous Klingsor. He has them do his bidding, and its pretty sexual in nature. No doubt watching the man toss blood around from the inside of a female genitalia (that is where Act two takes place, right?) is rather uneasy to watch in the current social mileu. That Parsifal comes in and liberates everyone might strike some as wrong for a number of reasons, but Girard isn’t trying to destroy the opera’s text either. But he ultimately does make a brilliant move in the final act to lend it social relevance and acceptance.

Act three reverts to the opening set, but with the world in abrupt turmoil. Time has passed and the knights have disbanded, forced to eat whatever they can find. A burial is taking place and the rules and divisions established in the opening act are completely eroded. Only Kundry, the symbol of “sin” in the world, is unable to cross the gap.

Then Parsifal arrives in an incredible theatrical coup, his silhouette generating a sense of mystery. As he draws nearer, he comes into the light and becomes clearer. The man who was a mystery is now the redeemer of all. From there the work moves into pure sublime beauty, Gurnemanz and Kundry washing the feet and brow of the weary Parsifal as he is hailed King and leader of the knights. Then Parsifal proceeds to help Kundry cross the chasm and be absolved of sin.

And to clinch it all, Kundry is the one to open the grail, a move often left to the men. While she dies, her evolution throughout the production explores women being allowed to return to their rightful place – as equals of men. In the final image of the night, as Parsifal lifts up the chalice, the stage is littered with men and woman together. They wear similar clothing and the gap in the ground is barely recognizable. A new society begins with the inequality done away with.

But Girard isn’t even finished there because in the very final moment of the piece, with Parsifal lifting the chalice, two figures stand amidst the kneeled crowd. One is Amfortas, the former King whose sin caused the turmoil of the brotherhood. The other is a woman clad in black. There are a few people still porting the black, but most are clad in white. The woman stands out amidst this crowd. And with the curtain dropping, Parsifal turns and glances in her direction. It leaves the viewer with a lot of questions. Is this a new Kundry and is Parsifal to follow Amfortas’ path, resetting the cycle back? Or is this the sign of progress? Of a woman set to come and rule alongside Parsifal? It is a brilliant touch that avoids leaving this seemingly positive outlook filled with a tinge of ambiguity. Life isn’t so simple, afterall.

One final note – after seeing blood flow throughout the chasm in the opening act, the final imagery showcases water. Human’s open wound has been closed and the sacred fountain restored.

Return of the Titans

The cast is absolutely sensational in every respect. Four years ago, Peter Mattei and René Pape reigned supreme as Amfortas and Gurnemanz respectively.

On Monday, they were even better.

Mattei was an absolute scene stealer every single time he was onstage, his voice ringing out imperiously into the cavernous Met. It’s almost impossible to believe that he didn’t have a microphone, so gargantuan was the ring throughout the theater. It was heartbreaking to hear this glorious sound usher out one pained phrase after another and yet Mattei always sustained incredible sense of technical precision. He built up his monologue so beautifully, each phrase more tortured than the previous one that his cries of “Erbarmen! Erbarmen!” were sublime climaxes to it all. He had even greater desperation, but also a more tragic sense of loss in the third act, jumping into the tomb in the ground, his movements more erratic at times and yet his voice softer and more muted. But the moments where he is called upon to blast out in increased pain showed him even more potent and forceful vocally.

The same could be said for Pape, who was clarity embodied as Gurnemanz. The character’s main role is as the narrator of the opera and the emotional range is limited at best in the opening act. However, his gentle nature came through in the final act in his interactions with Parsifal, his gloriously rich bass sound at its finest. His physicality was also rather telling, Pape imbuing the character with a signature pacing movement throughout the opening act, only to show that same movement impaired and weaker in the final third of the opera. It added to the sense of Gurnemanz being somehow broken over the failures of the knights.

Evgeny Nikitin returned to the role of Klingsor and relished it. His voice was pointed, vicious and his movements were in direct contrast with everyone else onstage. He had no qualms about moving with snakelike precision. His scene with Evelyn Herlitzius’ Kundry is simply exquisite in how the two voices blasted sound at one another in visceral confrontation.

Ever Thrilling & Fascinating

Speaking of Herlitzius, the German soprano was making her North American and Metropolitan Opera debut. Her voice isn’t a pretty sound whatsoever. One could even define it as abrasive, with a sharp vibrato that wobbles a bit in the upper range. But one could never accuse her of being boring or uninteresting. In fact, she is the complete opposite. Her Kundry was completely unhinged from the start, her exaggerated laughs and moans always off-putting for the viewer, but adding to the interest. You always wanted to know what she was going for and where she was going with the character. And she showed some tremendous range. She was overpowered in her fight with Klingsor, even if vocally she gave it her all and put up quite the fight. In her seduction of Parsifal, she was alluring and sensual. But when rejected, she was the embodiment of “hell hath no fury as a woman scorned,” her singing blistering in its power and strength. It was endlessly thrilling to see her rise into the soprano stratosphere, even if it wasn’t always pretty.

Victory Through Compassion, Not Power

Speaking of pretty, let’s talk about Klaus Florian Vogt, whose interpretation was simply beautiful. To some his voice seems out of place in a Wagner opera. I’ve even heard of him as being a “pushed-up Tamino.” It might all be completely right and at the same time it doesn’t matter. When writing his operas, Wagner called for bel canto style singing in the vein of his beloved Bellini. We don’t usually get that from tenors, mainly because the heavy and thick voices we are accustomed to can’t quite carry lines in that manner or with that “bel canto” beauty. But Vogt’s does. Moreover, his voice carries tremendous weight that cuts through the orchestra quite splendidly. His “Amfortas! Die Wunde!” was a perfect example of this, the delicate timbre suddenly thick and potent. But the true beauty of a passage such as this one was the sense of expansion of the line, giving the passage true anguish and introspection. And because of the complexion of his voice, Vogt could add nuance and layers to his Parsifal as a true “innocent fool.” Whereas other heroic tenors can’t genuinely sound like an innocent or pure man, Vogt can and he used it to his full advantage. One such example was the climactic showdown with Klingsor where with his hand raised he stops the wizard in his tracks and utters, “Mit diesem Zeichen bann’ich deinen Zauber.” He could have taken the approach of belting out this power declaration of victory, but instead opted for gentleness. At the end of the opera, Parsifal wins and unites the world through compassion, not strength. And in his greatest moment of victory over evil, he wins not through brute force, but through this very same emotion. The choice by Vogt is potent and insightful all the same. He brings a similar vocal quality in his final scene, furthering the point of Parsifal’s victory coming through compassion and love and not the violence and might of such Wagnerian heroes as Siegfried or Tristan (ironically, these heroes ultimately find death after said victories).

Musical Introspection

It is often said that, in Schopenhauerian terms, Wagner’s music could be described as “the will” personified. But in “Parsifal,” one might be more inclined to say that the majority of the music is the “abnegation” of said will. Instead of incessant brooding and propulsive momentum, Wagner’s last score is gentle, subdued, and even ponderous. It doesn’t move anywhere all that quickly (except for Act two), more interested in living in the moment, as Gurnemanz notes, where time becomes space. And it seems that maestro Yannick Nézet-Séguin approaches the score with this gentle nature in mind. His tempi tend to be broad, particularly when Wagner calls for lengthy pauses. You could feel the spacing throughout the prelude, the silences introspective and invitations to dig deeper. But what made his interpretation truly unique was the overall restraint you could feel. The entrance of the knights to close out the opening act did not emphasize the march-like nature that is often given grandiosity in other interpretations. Here it remained subdued, the transition more focused on the shift in mood. That isn’t to say that he wasn’t aggressive or didn’t push the Met Orchestra to its full voluminous potential. The music frayed and blistered powerfully throughout the second act as the tensions grew. But it all came back to the level of sublime tenderness in the final act, the final phrases simply divine.

There were a few orchestral misfires to be honest, with the brass section audibly uncomfortable and out of sync on some cues, but this is likely to improve with each passing performance.

So yes, this night was truly mesmerizing and for the second time in as many tries the Metropolitan Opera has a true winner with François Girard’s “Parsifal.” It is undeniably the finest Wagner production at the Met right now and the hope is that the director will come back and direct another production at such a high level. It also helps to have such an incredible cast in the ranks.