It was hard to know exactly what to make of San Francisco’s new “Salome,” with its three competing elements. Luisotti was hired “to reinvigorate the core Italian repertory that is San Francisco Opera’s birthright,” general director David Gockley writes in his program book message. Each season, Luisotti will conduct one “breakout” non-Italian work that Gockley feels appropriate, and this “Salome” was his first time leading a German opera, which he did in lyrical and luminous fashion.

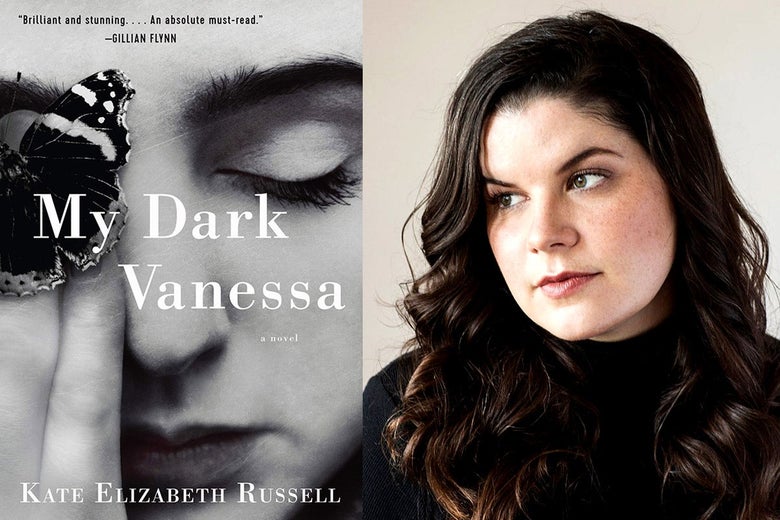

Nadja Michael was presumably brought in for something a little raunchier. Last year the German soprano was a sensation in a London production of the Strauss opera that took as its inspiration Pier Paolo Pasolini’s incomparably perverse film, “Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom.”

The new “Salome” comes by way of Opera Theatre of Saint Louis and was considerably tamer. Directed by choreographer Seán Curran, with dramaturge help from James Robinson, it looks back to the early 20th century dancers and choreographers Martha Graham, Isadora Duncan and Ruth St. Denis, especially in the “Dance of the Seven Veils.”

Michael may seem the ideal Salome. A former competitive swimmer, she is fit, moves well and carries off revealing costumes with ease. She is not without life experience, either. Born in Leipzig, she escaped from East Germany as a teenager not much older than Salome’s age, in the trunk of a car. She has the lung power to carry over Strauss’ immense orchestra.

Whether she is a sexy Salome may be a matter of taste, and that happens to be a raging debate in the opera blogosphere. Curran keeps Michael on the move. The set by Bruno Schwengl is an angular box focused towards a huge vault, the cistern in which John the Baptist is imprisoned. But Salome seemed more the prisoner in this space. A fidgety neurotic, she paced, pulled her curly hair, jumped, crouched and threw herself around like a crazed inmate in need of a straight jacket.

There may be more than one way to read this, but the production felt to me misogynistic by explaining away Salome’s behavior as craziness. Strauss may not excuse Salome’s behavior in his opera, but he makes her alluring and seductive through a score that explores a dark side of human sexuality.

Allowed a little more chance to focus on her singing, Michael may well have had fewer pitch problems, even as she thrived on the athletic challenges. After a clumsy but aerobic “Dance of the Seven Veils” (full of Duncan and Graham references), Michael was pumped up for her big final scene kissing John’s head, which she fondled and put between her legs in what was, finally, an impressive moment of real debauchery and amazing singing.

Strongest among the rest of the cast were Kim Begley’s lurid Herod and Irina Mishura’s iron Herodias. Greer Grimsley John sounded most imposing when singing through a megaphone off stage.

Curran presented the Five Hebrews, who argue about good and evil, as modern Hassidic Jews who notably (and perhaps offensively) stood out in a production that was not historically specific. There was, though, a Jesus-like figure, perhaps meant as a counterbalance. But unlike the Five Hebrews, he didn’t noticeably leer at Salome.

Were Curran looking for counterbalances, he had better material with a soft-edged conductor (who got gorgeous playing from the orchestra) and an edgy Salome. Unfortunately, though, there was no exciting offset between graceful conducting and an opera that falls far from grace.

-- Mark Swed

"Salome," San Francisco Opera, 301 War Memorial Opera House, 301 Van Ness Ave., San Francisco; 8 p.m. Saturday, Oct. 27 and 30; 2 p.m. Nov. 1; $15 -$310; (415) 864-3330. Running time 1 hour, 44 minutes.

Photo: Nadja Michael performing the "Dance of the Seven Veils" in San Francisco Opera's "Salome." Credit: Terrence McCarthy/San Francisco opera

&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&

It was a powerful performance that the San Francisco Opera

brought on stage with Salome. Nicola Luisotti took up the challenge to give

life to one of the most shocking Biblical stories as imagined by Oscar Wilde

and Richard Strauss. And, if not consistent in all its elements, this Salome

was an intense spectacle with many memorable singing moments supported by a

vivid orchestral rendition.

As the audience took their seats, the curtains were already

open. Spectators had time to familiarize themselves with the minimalist mise en

scene by Bruno Schwengl before the clarinet started its first uncanny scale of

Strauss' piece. Herod's guards were patrolling the space on stage while, in the

pit, a peculiar, prolonged tuning took place: the instrumentalists were

creating a disharmonious soundtrack that matched the eerie atmosphere on stage.

I noted that the audience was given the chance to

familiarize itself with the space in which the action unfolds. Yet, this is not

the most appropriate term for a work saturated with uncanny motives. In a

recent conversation reported in the programme notes, Luisotti commented on some

of the most striking qualities of Salome: not only are many of the characters

voyeurs, but this opera more than others 'makes us voyeurs, which in secret we

might like, but to admit is uncomfortable. […] It's a private opera; everything

happens in one room'.

Voyeurism and gaze were certainly themes explored in this

production. The set was a sombre box-like space recalling a darkroom. This

photographic parallel was amplified by the door of the prison from which

Jochanaan appears: an oversized camera lens. This reading is consistent with the

lingering on images of gaze present in Oscar Wilde's play, the source from

which this opera draws most of his textual material.

Director Seán Curran made good use of these elements: having

moved from choreography to stage direction, he conferred to this production a

coherence made of gazes wittingly choreographed. At times the minimalist, bare

staging seemed not to serve the many layers of the opera. Yet, the staging

managed to assume consistent connotations precisely because of the way the

characters inhabited it. In particular, in the first scene the narrative,

tension was conveyed through proficient and intense singing by Garrett Sorenson

(Narraboth), Elizabeth DeShong (the Page) and by the interactions of body and

gaze between the characters.

What really made the theatrical space come alive was the

presence of Nadja Michael in the title role. The audience, together with the

characters inhabiting the drama, first saw Michael's Salome in a flowing,

virginal white dress, which clashed with the provocative way she swung around

the guards, giving life to bodily and vocal patterns. She portrayed a whimsical

and manic teenager. Unfortunately, her high tessitura is still a bit strained.

This aspect of her singing should improve as she continues to transition from

mezzo to soprano.

On the other hand, her physicality helped her in the

construction of a fierce character. Even when not singing, she functioned as a

catalyst for narrative tension – for instance, when she was sitting immersed in

her thoughts, by manically touching her hair. Her making love to Jochanaan's

head at the end of the drama was a masterpiece of morbid intensity.

Shape patterns – oval shapes in particular – were a strong

motif in this production. Both the main entrance at the left of the stage and

Jochanaan's prison were round-shaped; and Salome could penetrate the prophet's

prison through a round opening. Moreover, the moon, whose image permeates

Wilde's text, was a big circle of light projected on the stage, and to which

Salome seemed to be attracted. Like a moth, Michael's Salome delivered her

lines swaying around the circumference of this aseptic and omnipresent moon.

Powerful moments certainly included those featuring baritone

Greer Grimsley. He aptly exploited all the colours of his role. His Jochanaan

was an imposing presence on stage, and his timbre and vocal precision conveyed

nobility and moral steadiness, together with a sense of endured suffering,

which befits the portrayal of this character.

Kim Begley's Herod wasn't equally convincing. Although

elegant in his phrasing, he was often surmounted by the orchestra. His Herod

was a red-blooded pathetic man, and his ineptitude was manifested well in his

relationship with his step-daughter, who seemed almost to intimidate him.

On the other hand, I felt he could have exploited more the

interaction with Salome: in this regard, his portrayal came across as somewhat

weak. This was not the case for Herodias, Salome's mother: through her precise

and violent singing, Irina Mishura portrayed a powerful and scornful character.

This was the first time Luisotti conducted this opera, but I

found his reading of the score a generally convincing one. From the pit, the

conductor and his musicians created a harmonious oscillation between vigorous

outbursts of sound and of pianissimo lines.

There were a moments, though, in which I wished Luisotti

would push more to the extreme the depth and colours of Strauss' score. One of

these moments, perhaps, was the Dance of the Seven Veils. As Salome dares to

fulfil the lustful desires of her step-father to get what she desires, Luisotti

could have dared to venture into subtler shades of the musical fabric.

Incisiveness was the missing ingredient in some moments. Yet, as I noted above,

it is evident that Luisotti engaged with Strauss' score from a passionate and

knowledgeable perspective.

As my friend noticed after the performance, we are lucky to

take our seats at the opera house knowing pre-emptively of Salome's

necro-nymphomaniac whims and of the way Strauss gave musical shape to them. His

work has not lost its shocking qualities, but it is each company's

responsibility to bring the intensity of the score alive. This San Francisco

Opera Salome had the potential to become a truly powerful interpretation, but

some elements are not totally convincing. Nonetheless, thanks to some thrilling

vocal renditions, and to Luisotti's fiery reading of the score, this one is a

Salome worth catching.

Director

Seán Curran made good use of these elements: having moved from choreography to stage direction, he conferred to this production a coherence made of gazes wittingly choreographed. At times the minimalist, bare staging seemed not to serve the many layers of the opera. Yet, the staging managed to assume consistent connotations precisely because of the way the characters inhabited it. In particular, in the first scene the narrative, tension was conveyed through proficient and intense singing by

Garrett Sorenson (Narraboth),

Elizabeth DeShong (the Page) and by the interactions of body and gaze between the characters.

What really made the theatrical space come alive was the presence of Nadja Michael in the title role. The audience, together with the characters inhabiting the drama, first saw Michael's Salome in a flowing, virginal white dress, which clashed with the provocative way she swung around the guards, giving life to bodily and vocal patterns. She portrayed a whimsical and manic teenager. Unfortunately, her high tessitura is still a bit strained. This aspect of her singing should im

Kim Begley

Kim Begley's Herod wasn't equally convincing. Although elegant in his phrasing, he was often surmounted by the orchestra. His Herod was a red-blooded pathetic man, and his ineptitude was manifested well in his relationship with his step-daughter, who seemed almost to intimidate him.

On the other hand, I felt he could have exploited more the interaction with Salome: in this regard, his portrayal came across as somewhat weak. This was not the case for Herodias, Salome's mother: dgeable perspective.

As my friend noticed after the performance, we are lucky to take our seats at the opera house knowing pre-emptively of Salome's necro-nymphomaniac whims and of the way Strauss gave musical shape to them. His work has not lost its shocking qualities, but it is each company's responsibility to bring the intensity of the score alive. This San Francisco Opera

Salome had the potential to become a truly powerful interpretation, but some elements are not totally convincing. Nonetheless, thanks to some thrilling vocal renditions, and to Luisotti's fiery reading of the score, this one is a

Salome worth catching.

Photos credits: Cory Weaver

Director Seán Curran made good use of these elements: having moved from choreography to stage direction, he conferred to this production a coherence made of gazes wittingly choreographed. At times the minimalist, bare staging seemed not to serve the many layers of the opera. Yet, the staging managed to assume consistent connotations precisely because of the way the characters inhabited it. In particular, in the first scene the narrative, tension was conveyed through proficient and intense singing by Garrett Sorenson (Narraboth), Elizabeth DeShong (the Page) and by the interactions of body and gaze between the characters.

Director Seán Curran made good use of these elements: having moved from choreography to stage direction, he conferred to this production a coherence made of gazes wittingly choreographed. At times the minimalist, bare staging seemed not to serve the many layers of the opera. Yet, the staging managed to assume consistent connotations precisely because of the way the characters inhabited it. In particular, in the first scene the narrative, tension was conveyed through proficient and intense singing by Garrett Sorenson (Narraboth), Elizabeth DeShong (the Page) and by the interactions of body and gaze between the characters. Kim Begley's Herod wasn't equally convincing. Although elegant in his phrasing, he was often surmounted by the orchestra. His Herod was a red-blooded pathetic man, and his ineptitude was manifested well in his relationship with his step-daughter, who seemed almost to intimidate him.

Kim Begley's Herod wasn't equally convincing. Although elegant in his phrasing, he was often surmounted by the orchestra. His Herod was a red-blooded pathetic man, and his ineptitude was manifested well in his relationship with his step-daughter, who seemed almost to intimidate him.  As my friend noticed after the performance, we are lucky to take our seats at the opera house knowing pre-emptively of Salome's necro-nymphomaniac whims and of the way Strauss gave musical shape to them. His work has not lost its shocking qualities, but it is each company's responsibility to bring the intensity of the score alive. This San Francisco Opera Salome had the potential to become a truly powerful interpretation, but some elements are not totally convincing. Nonetheless, thanks to some thrilling vocal renditions, and to Luisotti's fiery reading of the score, this one is a Salome worth catching.

As my friend noticed after the performance, we are lucky to take our seats at the opera house knowing pre-emptively of Salome's necro-nymphomaniac whims and of the way Strauss gave musical shape to them. His work has not lost its shocking qualities, but it is each company's responsibility to bring the intensity of the score alive. This San Francisco Opera Salome had the potential to become a truly powerful interpretation, but some elements are not totally convincing. Nonetheless, thanks to some thrilling vocal renditions, and to Luisotti's fiery reading of the score, this one is a Salome worth catching.