Carmen review – Bizet meets Busby Berkeley

Royal Opera House, LondonBig numbers and bohemian loucheness characterise Barrie Kosky’s uneven production

Barrie Kosky’s new Royal Opera production of Carmen hails from Frankfurt, where it was first seen in June last year. It’s a curious staging, shot through with flashes of brilliance, though by no means cohering into a musical or dramatic whole.

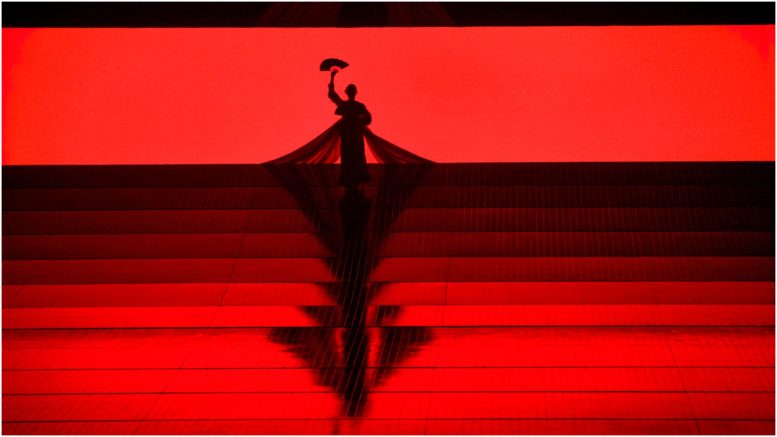

As one might expect, Kosky aspires to postmodern radicalism. He has largely dispensed with Spain, apart from a few flounced frocks and matador uniforms. Don’t expect a tobacco factory or cigarette girls smoking, or indeed anything that smacks of particularly French naturalism. Instead, Kosky pushes towards the trappings of the Broadway musical or the Weimar Republic revue. Katrin Lea Tag’s set is a vast staircase out of Busby Berkeley. The costumes suggest the 1930s. Anna Goryachova’s Carmen is first seen, gamine and androgynous, in a pink toreador’s outfit. Later, her costumes hint at Hollywood or Weimar glamour, with overtones of Dietrich in Sternberg’s Blonde Venus and Louise Brooks as Georg Pabst’s waif-like Lulu in Pandora’s Box.

Kosky’s choreographer for the big show numbers, of which there are many, is Otto Pichler, who has provided cast, chorus and six dancers with sinewy hand-jiving routines, some of which are very camp, though the Chanson Bohème at the start of act two has wonderful loucheness. Kosky’s imagery is often most striking, however, in the more intimate scenes. In act one, Francesco Meli’s José chillingly controls Carmen after her arrest by pulling her around with ropes from the top of the staircase, while she flails at the bottom. Later, his attempts to prevent her walking up it by standing on her train are the prelude to murder.

Kosky plays fast and loose with the score, arguing that Bizet never made a definitive edition of Carmen. He restores a number of passages cut before the 1875 premiere, so Gyula Nagy’s Moralès gets to sing his act-one couplets about fidelity, and Goryachova gives us both the familiar Habanera and the tarantella setting of the same text, which Bizet excised at the insistence of Célestine Galli-Marié, who created the title role. Kosky has also, however, replaced the dialogue with narration, whispered over a sound system by the actor Claude De Demo, and all too frequently proving intrusive.

Musically, meanwhile, things are uneven. Goryachova and Meli are more convincing in the later scenes as their relationship sours, than earlier on when we don’t quite understand what draws them together. Goryachova radiates cool poise and self-assurance. Some of her high notes, however, can be a bit unsteady and vocally she’s at her best being suggestive with Kostas Smoriginas’s Escamillo or heaping scorn on Meli as he becomes too possessive. His singing can be ungainly, very loud or very soft, with little in between.

More consistently successful are Smoriginas and Kristina Mkhitaryan as Micaëla. He makes an attractive, silky voiced Escamillo. Mkhitaryan, with her warm even tone, sounds glorious. In the pit, conductor Jakub Hrůša favours extreme speeds; there’s plenty of panache in the dances and ensembles, though he dawdles over both Micaëla’s duet with José in act one and the Flower Song in act two. The Royal Opera Chorus, though, have a terrific time flinging themselves into the big routines with gusto and glee, and their singing is exceptional.

&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&

Love it or hate it, this isn't just another

Carmen - Royal Opera,

Anna Goryachova as Carmen at the Royal Opera

House CREDIT: ALASTAIR MUIR

•

Rupert Christiansen

7 FEBRUARY 2018 • 12:01PM

Having first encountered Beecham’s peerless

recording in short trousers and reviewed more than 30 productions, I smugly

considered myself pretty familiar with every note of Bizet’s Carmen – often ad

nauseam, as it tends to be sloppily performed.

One great virtue of Barrie Kosky’s new staging,

imported from Frankfurt , is that it has shaken

my complacency – it is certainly different. But being different is not quite

enough, and I felt increasingly dissatisfied as the evening progressed.

Things get off to a terrific start. The stage is

filled with a wide, steep staircase, used to stunning effect as the chorus

cascades down or hares up its steps. There is only minimal indication of

anything Hispanic, and none at all of the gipsy or cigarette factory. Instead,

the first act is played out like a Parisian floor show in which Carmen is the

chic androgynous star, flanked by dazzling showbizzy dance routines.

–––

There is much musical material, excised from the

standard editions, that I hadn’t previously heard – notably another entrance

aria for Carmen, a comic aria for Moralès, and a much longer duet for José and

Micaela. Some of this is delightful, some better left in the library. The

spoken dialogue is replaced by an off-stage narration, using French text mostly

drawn from the opera’s source in Mérimée’s novella. It’s all electrically

alive, fresh, witty, energised and provocative.

Gradually, however, as so often with Kosky’s

work, it loses steam: the first two acts last nearly two hours, and there is

less new music to keep one alert. As Carmen capriciously changes her costume

and identity and those high-kicking chorus lines (a Kosky trademark) become

tedious, one begins to miss the sense of a specific social context or

psychological reality. By the end, it’s become an elegantly clever exercise in

Brechtian theatricality rather than an involving emotional drama.

Russian mezzo Anna Goryachova is a petite, edgy

and dangerous Carmen, who tires vocally in the latter stages. As José,

Francesco Meli is miscast – a robust Italian tenor over-egging a French

confection. Kristina Mkhitaryan shrieks the climax of Micaela’s aria; Kostas

Smoriginas makes a passable Escamillo.

There is wonderfully translucent orchestral

playing, delicately conducted by Jakob Hrusa – the Act 3 Prelude is magically

beautiful and the overall approach has tingling clarity and verve. The

smugglers’ quintet is exemplary, and both the adult and children’s chorus are

thrilling.

So on balance, it’s thumbs half up. Love it or

hate it – love it and hate it, indeed, as I did – at least you can’t say that

it’s just another Carmen.

&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&

Please use the sharing tools found via the email icon at the top of articles. Copying articles to share with others is a breach of

FT.com T&Cs and Copyright Policy. Email licensing@ft.com to buy additional rights. Subscribers may share up to 10 or 20 articles per month using the gift article service. More information can be found here. https://www.ft.com/content/20f81bcc-0cc2-11e8-8eb7-42f857ea9f09

Carmen, Royal Opera House — a wake-up call met with boos and cheers Barrie Kosky’s radical production of Bizet’s opera is a sharp contrast with its predecessor Francesco Meli as Don José and Anna Goryachova as Carmen. Photo: Bill Cooper Share on Twitter (opens new window) Share on Facebook (opens new window) Share on LinkedIn (opens new window) Save Save to myFT Richard Fairman FEBRUARY 8, 2018 4 It does not take a gypsy fortune-teller to predict that a new production of Carmen is likely to be flawed. The cards are stacked against the director who has to wrestle with the work’s uneasy mix of dialogue and grand opera, of light-hearted musical and gutsy realism. In bringing Barrie Kosky’s Frankfurt production of Carmen to London, the Royal Opera has uncharacteristically opted for some radical answers. Kosky is a director who likes to shake things up, which will explain the boos among the cheers at final curtain. He started by taking two big decisions, and neither was a good one. The first involves adopting swathes of music discarded or re-written by Bizet before the premiere, so we get, for example, two versions of Carmen’s entrance aria, one after the other. The second was to replace the dialogue with a spoken narration, drawn from Mérimée’s novella, which kills the drama stone dead. The protracted first half feels as if it will never get going. It is not for want of trying. Kosky has ditched the usual Carmen clichés and taken the opera for a night out at the Folies Bergère, pepping up the party atmosphere with a chorus line, disco dancers and a celebrity appearance by a gorilla (don’t ask who). The showbiz razzle-dazzle of it all is hugely brash and self-confident. But a high price is paid: when everything is a cabaret number, the relationships at the opera’s heart get lost along the way. It is a relief that Carmen herself, charismatically sung and played by Anna Goryachova, is able to hold her own. Francesco Meli veers between gentle delicacy and searing intensity, sometimes from phrase to phrase, but his Don José has straightforward commitment. Kristina Mkhitaryan is a touching, vulnerable Micaëla and Kostas Smoriginas a not-quite-magnetic Escamillo. Pierre Doyen and Jean-Paul Fouchécourt, as Le Dancaïre and Le Remendado, stand out as two authentically French voices (would there were more) and conductor Jakub Hrůša keeps the orchestra sounding slim and trim, though he is apt to linger. After the dreary, traditional production the company had previously, this comes as a wake-up call. Think of it as an alternative Carmen, exploring the opera’s artistic hinterland — a Carmen through the looking glass. All the Royal Opera needs now is a new production of Bizet’s standard masterpiece.

Carmen, Royal Opera House — a wake-up call met with boos and cheers Barrie Kosky’s radical production of Bizet’s opera is a sharp contrast with its predecessor Francesco Meli as Don José and Anna Goryachova as Carmen. Photo: Bill Cooper Share on Twitter (opens new window) Share on Facebook (opens new window) Share on LinkedIn (opens new window) Save Save to myFT Richard Fairman FEBRUARY 8, 2018 4 It does not take a gypsy fortune-teller to predict that a new production of Carmen is likely to be flawed. The cards are stacked against the director who has to wrestle with the work’s uneasy mix of dialogue and grand opera, of light-hearted musical and gutsy realism. In bringing Barrie Kosky’s Frankfurt production of Carmen to London, the Royal Opera has uncharacteristically opted for some radical answers. Kosky is a director who likes to shake things up, which will explain the boos among the cheers at final curtain. He started by taking two big decisions, and neither was a good one. The first involves adopting swathes of music discarded or re-written by Bizet before the premiere, so we get, for example, two versions of Carmen’s entrance aria, one after the other. The second was to replace the dialogue with a spoken narration, drawn from Mérimée’s novella, which kills the drama stone dead. The protracted first half feels as if it will never get going. It is not for want of trying. Kosky has ditched the usual Carmen clichés and taken the opera for a night out at the Folies Bergère, pepping up the party atmosphere with a chorus line, disco dancers and a celebrity appearance by a gorilla (don’t ask who). The showbiz razzle-dazzle of it all is hugely brash and self-confident. But a high price is paid: when everything is a cabaret number, the relationships at the opera’s heart get lost along the way. It is a relief that Carmen herself, charismatically sung and played by Anna Goryachova, is able to hold her own. Francesco Meli veers between gentle delicacy and searing intensity, sometimes from phrase to phrase, but his Don José has straightforward commitment. Kristina Mkhitaryan is a touching, vulnerable Micaëla and Kostas Smoriginas a not-quite-magnetic Escamillo. Pierre Doyen and Jean-Paul Fouchécourt, as Le Dancaïre and Le Remendado, stand out as two authentically French voices (would there were more) and conductor Jakub Hrůša keeps the orchestra sounding slim and trim, though he is apt to linger. After the dreary, traditional production the company had previously, this comes as a wake-up call. Think of it as an alternative Carmen, exploring the opera’s artistic hinterland — a Carmen through the looking glass. All the Royal Opera needs now is a new production of Bizet’s standard masterpiece.

&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&

“We don’t need to worry about what country are we in,” Barrie Kosky told the designer for his new production of “Carmen” at the Royal Opera in London. “We can do whatever we bloody well like.”

Monika Rittershaus

LONDON — “Everyone assumes ‘Carmen’ is what people are used to,” Barrie Kosky said in a recent interview. “A big Spanish spectacle: loud, huge orchestra, huge chorus. Lots of Spain.”

In his production of Bizet’s classic work, which opens at the Royal Opera House here on Feb. 6 and runs through March 16, Mr. Kosky has stripped away the castanets and other clichés.

Born in Melbourne, Australia, Mr. Kosky is known for his highly individual, theatrical style, which combines the seriousness of high-concept “director’s theater” with a healthy dose of campy razzle-dazzle.

Since 2012, Mr. Kosky, 50, has been the artistic director of the Komische Oper in Berlin, a company once seen as the distant third of the city’s three opera houses — but now regarded, under his leadership, as one of the world’s most interesting. Mr. Kosky’s programming there has been eclectic, including Broadway musicals like “West Side Story” and “Fiddler on the Roof”; the comic operettas of Offenbach; and works by forgotten composers such as Oscar Straus and Paul Abrahams.

During a rehearsal break, Mr. Kosky discussed his “Carmen.” Here are edited excerpts from the conversation.

ADVERTISEMENT

“Carmen” has been performed hundreds of times here at the Royal Opera, but your version is different. How?

First, you’ve got to understand that there’s no definitive version of “Carmen.” The printed score was done after Bizet’s death, and we know that there’s a handwritten score, which was then changed in rehearsal. Those rehearsals were a catastrophe: The chorus went on strike, the orchestra couldn’t play the music, Bizet had to change the ending. The management kept saying, “You can’t do this, you can’t do that.” When he died, there was no definitive version.

One of the differences in our version is that we stick with the idea that the piece was written with spoken dialogue between the musical elements, because it was an “opéra comique.” But we don’t do spoken dialogue between the characters; we have a narrator.

You seem very interested in opéra comique and operetta, traditions of music theater that many big opera houses shy away from. How does “Carmen” fit into those?

The piece is not a Spanish opera. It’s a French opera, from the first note. Actually it’s not even a French opera, it’s an operetta that turns into an opera in the fourth act.

This is the mistake that people make. They assume that it’s a doom-laden story of a Gypsy with black curly hair and gold earrings, and a story of love and sex and whatever. Well, it turns into that, but for the first two thirds of the evening, it’s sunlight, it’s joy, it’s naughtiness, it’s irony. I keep saying to the cast, “You’re in an operetta. You are not in ‘le grand opéra.’ ”

But the opera comes to us so steeped in all these Spanish clichés.

We play with the Spanish clichés. For example, I said to my designer, “We are not setting the production in any place. We don’t need to worry about what country are we in; we can do whatever we bloody well like.” And that opens you up to all sorts of things. But I said, “Let’s just put Escamillo in a fabulous toreador’s costume.” When he comes on, everyone’s waiting for that number — and we turn it into a huge number. I said, “Just make sure the toreador costume looks fabulous, and it solves the problem.”

A lot of the Spanish flavor comes from dance rhythms in the music: The overture opens with a pasodoble, there’s the famous “Habanera,” and so forth. What role does dance play in your “Carmen”?

As you say, it’s in the music. She dances, and we’ve put other dance elements in, in places where there’s not normally dancing.

She uses dance but not in the form of go-go dancing: It’s not pole dancing, and it’s not the local men’s night, with a stripper there. She uses dance in the absolute primal sense of a kind of Dionysian expression of joy and power, which is an entirely different thing.

Earlier this year, in a production of “Carmen” in Florence, there was a lot of controversy when the ending was changed so that she kills Don José, and not the other way around. What do you think about that?

I’m a little bit cynical because I think it was very connected to the whole #MeToo movement. I mean there have been thousands of productions in the last hundred years where people change the ending. There have been thousands where it says in the libretto that she dies, and a production makes him die. This is nothing new.

If people think that that’s contributing to a debate about #MeToo, then I roll my eyes in enormous cynicism, because the #MeToo moment is very important: It has to do with what is happening in the offices and streets and corridors of real life. But we are in the fantasy space of theater.

When you make decisions about what to do onstage, do you think about the statements these make, politically?

I’ve got to think about it, because I’m a man who lives in the 21st century. We’ve got to be honest here: The history of opera is a history of misogyny. With glaring exceptions — Monteverdi, Mozart, Janacek — most of the rest, particularly the 19th century, is deeply problematic.

You have a duty as a director, male or female, to investigate that and try and twist it or try and play with it or try and subvert it. That’s what makes opera so fantastic. You operate in opera on many different levels. You are having a conversation with the past, on a stage, to a contemporary audience. This is what makes it exciting.